1st International Conference ‘A favor de lo mejor’ [In favour of what is best, in media], National Auditorium, Mexico City, D.F.

Panel: The horizon ahead (for mass media), April, 21st, 1999, 5pm.

Transcription –corrected by author:

¿WHEN AND WHY MEDIA DIE…?

Along the centuries, many wars have been fought on paper; let us now talk about those spontaneously fought by consumers…I have very little time to convey to you the results of 14 years of research –14 years during which I have studied what people want to see and hear in the media. Today I will present what I consider the most surprising conclusion arising from my work, something even I could not anticipate at the outset of my studies.

I will limit myself to the discussion of this one discovery, because you, my audience, comprise 10,000 people –all having different ideas, ages, professions, opinions, origins and religions. Plus, you have come in search of a message –not a lot of data or names. Finally –additionally, I trust this one issue, idea, concept, will suffice to convince you that we can change media, and thus change Mexico, for the better of us all –media included.

A long time ago –and I’m speaking now about the 15th century– a great social campaign was undertaken, similar to that which brings us together today. Naturally, society –in the 15th century, was not concerned with television or radio contents, but rather with the great chivalric romances of the time, which were usually characterized by a certain degree of the fantastic and in which the hero strove to obtain fame for his deeds in order to merit the love of his beloved. The novels were about princes and princesses, heroes, dragons to be slain… The hero’s primary objective was to prove himself worthy of his beloved and to honor her with his bravery and his victories against evil. Meanwhile, the lady also had to demonstrate that she was deserving of the hero’s love and fidelity. Of course, there was always a happy ending.

There were no explicit scenes of sex or violence, nor inappropriate language in keeping with today’s standards; nevertheless, guess what? People complained about the abuse, precisely, of sex, violence and inappropriate language! To clarify: Society complained about the negative effects of these works on children and young people… To help you calibrate the powerful impact of these chivalric romances on the adults of the time, you have only to take note that the Calafia Valley in California and the Amazon River in Brazil were so named by the European conquerors, because these names were included in the very works we are discussing. The brave people who came to America believed they were going to find in our lands those fantastic and mythical places which they had heard about in novels. Documents of the time demonstrate that those who financed the conquests expected to find the true land of the Amazons, the Land of Gold (“El Dorado”), or the fountain of youth. The impact of these novels –we can see, is undeniable, …with respect to the adults of the time as well as the young people.

Returning to the campaign against the chivalric romances, guess which social agents participated in it? Naturally, and as you already imagine, they were the very same ones who participate in similar campaigns today: Parents, civil authorities, religious figures, and –of course, the academic world. Were they right or wrong? I hope that at the end of this conference, you will be able to answer this question by yourselves.

These novels died out with the passage of time. They died because their producers and distributors refused to listen to the demands of their society –their readers, their consumers… When people felt ignored, rejected, perhaps even attacked; when they no longer recognized their personal and colective aspirations reflected in those stories, they stopped reading them –they closed their doors against them. Little by little, fewer and fewer of these novels were published, because fewer and fewer were being read –…consumed.

Time passed and the world moved on. Were there other episodes similar to that of these chivalric romances? Indeed there were! –many times.

Let us turn now to 20th century Mexico. Here, during the 1940’s and the 1950’s, we experienced “the Golden age of Mexican Film”. The movies made during that time were so successful –they achieved such strong and admirable levels of complicity and communication with the public, that even today, and with regularity, they comprise 40% of the most-watched films on Mexican television. In spite of this, their creators wanted to produce a “better” product (do not underestimate the importance of those quotation marks), they wanted to make things of a more “elite” nature –of greater prestige. They wanted to earn the respect of “serious” artists, and so they stopped producing such films. In spite of their efforts, they were unable to do without their public, and thus killed the “medium”, because the Mexican film industry has not recovered ever since (we need only study the ticket sales of the last 35 years to see how US films have gained a tremendous foothold in our market, while at the same time, the “old” Mexican films continue to be the most successful).

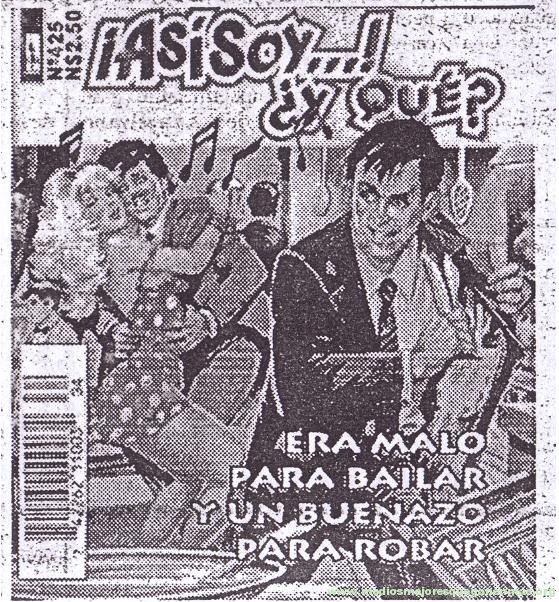

Ten years later, in the 1950’s, what popular work was most successful in Mexico? –the serialized melodramatic comic (or graphic) novel. Some of you will perhaps remember hearing of Pepín, Paquín, Chamaco chico, Chamaco grande (and a little later: Lágrimas, risas y amor). These stories –currently forgotten, published at the time of their greatest success, a new episode every day, and two on Sundays. Imagine the impact they had on our country… The editors themselves demonstrated to the Mexican Ministry of Public Education that many people learnt to read not only through them, but also because of them (in order to be able to read them).

Now, guess what happened to them, how they met their death, to such a degree as to have almost been erased from our memories. You guessed it! They underwent the same process as had the films of “the Mexican Cinema Golden Age” and the novels of the 15th century. When the Mexican serialized melodramatic comic novel (or graphic novel) was born, and during the first campaign registered by specialists, society asked for contents less hostile towards their values, ideas and beliefs. At the time of greatest glory, there arose a second campaign. With the third of these campaigns came the end of “the Golden Era” of the Mexican serialized melodramatic comic (or graphic) novel: Birth, development and death. Society –tired of demanding changes that never came, simply stopped buying the newer works. Now ask the producers and distributors of that particular market, whether it ever again experienced a comparable success. Never. Never again did the Mexican periodicals industry reach the levels of sales and market penetration that it experienced at the height of these magazines’ popularity, at a time when the Mexican population was scarcer, and much harder to reach.

If you would like to learn more about those magazines and their audience’s campaigns for change; about how interested parties played with the public thinking they could fool and manipulate people; if you wish to understand our country’s “public” (audience) better, I recommend that you read Bad language, naked ladies and other threats to the nation: A political history of comic books in Mexico, by historian and Cultural Studies specialist Anne Rubenstein, published in 1998 by Duke University Press (Durham and London). I may not agree with everything she concludes, but I certainly treasure the sizeable objective data she gatheredd.

I will not continue adding anecdotes to the ones we have already shared, so that this presentation does not exceed the allotted time. However, I would like to make one final comment regarding a film you have surely seen: Cinema Paradiso. Do you remember the story of a small-town movie theater which was born as a parochial theater in which the inhabitants of the whole town met and enjoyed together, and which eventually became an X-rated theater, frequented only by a small and anonymous public?

Do you recall how that started? With a kiss; it started with just one kiss! …Who would object to a little kiss? The whole town became stirred up when that first kiss appeared on screen at the theater –the religious minister no longer had anything to do with the cinema, of course! How could the village not have noticed something which had been systematically cut out from films since they could remember, and which many adults desired to see? However, the day that theater was no longer appropriate for underage audiences –according to the place, time and culture it was immersed in, the adult audience went into decline, too. When a kiss no longer caused such commotion –when it no longer attracted its viewers’ attention and brought them into the theather, it became necessary to show increasingly explicit scenes, until the personal limits of most viewers were surpassed –until each viewers’ personal barriers were trespassed. Once this happened, the theater lost many spectators and the “medium” died.

It is true that when we surpass certain limits, we may please a particular sector of society –a minoritarian one, compared to the mainstream one we were originally producing for. This means that we inevitably lose contact with the greater part of our viewers when we trepass those limits that are acceptable to most of them. Although this “showing-of-previously-limited material” may momentarily capture our audience’s attention (it may amaze them simply because of the transgression it entails, and because of how different it is to what most of us spontaneusly expect to find in such a work), it has proven to behave as a poor sales strategy on the long run.

And we want to live off and profit from “media”, not just one day, but for our entire lives…

In order to live off the “media”, we must live in contact –we must connect with, the majority of our “target” public (audience). We need to understand it, respect it, feel part of it, and listen to the people. The public is not an inert or passive entity which will tolerate all abuse and every attack. It is the public, indeed, that has the power in its pocket.

[Applause]

The question you are surely asking yourselves now is: “Why do mass ‘media’ sales behave this way, and why does the ‘medium’ die when it is no longer acceptable to the majority?”. There must be a reason…

And there is:

All social groups have Literature, even those that have no alphabet. This is true because Literature is necessary for the survival of society. Its appeal, in fact, is closely linked to its social function. Mass media nowadays fulfill this function, helping to reflect and keep alive the world view and the group values of all-or-most of their society’s members.

Literature’s goal, in fact, is to justify it emotionally and rationally “in action”, by way of narrations (story-telling). In other words: To show how worthy and useful these values, ideas and beliefs are, through the positive consequences they produce in the characters who live according to them.

That is why popular literature –mass media– enjoys commercial possibilities not available to other types of literature. That is also why, when we work in “media” but lose touch with society, we fail economically. If we do not fulfill our function and give voice to the values and world view of our society –our target market, we will dig our own grave: We will stop being useful to society.

A society’s world view comprises a series of strategies which, over centuries, have demonstrated their usefulness by facilitating the survival of that society in its territory, in its particular context. If we do not collaborate in the orderly survival of the social group, other “media” or another person will take our place, and will take that which we neither valued adequately, nor deserved.

[Applause]

In light of this definition of Literature –and of “media”, we can understand why the social agents organizing these campaigns –like that which gathers us today: In favour of what is best in media (A favor de lo mejor en los medios de comunicación), are always the same: Parents, schools and universities (Academia), religious and civil authorities. They represent the other social institutions which share –alongside with Literature- the obligation to transmit to the newer generations (and to those previous ones who lacked other access to it), the world view –the values, ideas and beliefs, that has proven useful to society.

They have an obligation to make their voices heard just as we are doing here today in this National Auditorium, to take exception when the free social institution that is Literature, instead of supporting the constructive coexistence and survival of society, refuses to fulfill that responsibility.

This also explains why the subjects of these campaigns are always the same, and why sex and violence always comprise their primary concern: Sociologically –that is, from the standpoint of the survival of the social group, when we do not pay attention to the arrival and education of the new members of society in the best possible context within our culture, when we do not work towards orderly and nonviolent coexistence within the community, we dig our own grave; we condemn ourselves to our own destruction.

[Applause]

This is the idea, the message, the concept I promised you at the beginning of this presentation: For Mexico to survive, we must live in an orderly manner. For Mexico to survive, it must remain embedded in its own world view and traditions, which, as I indicated earlier, comprise the strategies that have made its survival possible for centuries at a place and under circumstances where many different governments have not been able to survive.

For Mexico to live, it needs “media” –let us not forget that when one “medium” dies, another one takes its place–; but the “media”, without Mexico, cannot survive at all.

[Applause]

Thank you.

___ ___

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the following persons for material, information, support and guidance:

▸Enrica Schettini Piazza, Academia dei Lincei (Italy), and V.V. (r.i.p.), Centro di Ricerca Pio Manzù (ONU-Italy),

▸ María Cruz García de Enterría, Univ. de Alcalá de Henares (Spain),

▸ Francisco Guerra (r.i.p.), Academia de Doctores (Spain),

▸ Aurelio González Pérez , El Colegio de México and UNAM (Mexico),

▸ Concepción Company, UNAM and El Colegio de México (Mexico),

▸ María Dolores Bravo Arriaga, UNAM and Univ. Autónoma de Puebla (Mexico),

▸ Eugenia Revueltas Acevedo , y Abelardo Villegas (r.i.p.), UNAM and El Colegio de Michoacán (interview, November, 7th, 1998) (Mexico),

▸ Manuel Ignacio Pérez Alonso (r.i.p.), Univ. Iberoamericana-Mexico City campus, and Archivo Histórico de la Provincia de México-SJ (México),

▸ Joel Federman, Univ.of California-Santa Barbara (United States),

Yolanda Vargas Dulché (r.i.p.), Lágrimas, Risas y Amor (interview, November, 4th, 1998) (México),

▸ INRA, IBOPE y NIELSEN (TV and radio audience measuring and research companies) (México),

▸ Different advertising agencies (periodicals’ market information: consumption circulation and size of editions, etc.) (México),

▸Cámara Nacional de Comercio [National Chamber of Commerce] (Mexico),

▸ Humanidades [academic newspaper, while directed by Dr. Jaime Litvak King, r.i.p.], UNAM (Mexico),

▸ Gloria López de Cruz, SOGEM [Mexican Writers’ Guild] (Mexico),

▸ María Elena Pérez, SEP [Mexican Ministry of Education] (Mexico),

▸ Ana Lilia Villareal, ILCE [Latin American Educational Communications Institute] (Mexico).

___ ___

PAPER FIRST PUBLISHED BY

(BIBLIOGRAPHIC/HEMEROGRAPHIC/VIDEOGRÁPHIC SOURCE’S DATA):

Blanca de Lizaur; “¿Cuándo, y por qué, mueren los ‘medios’?”, in 1er Congreso Internacional “En los ‘medios’, a favor de lo mejor”, co-sponsored by over 2000 instituciones, in order to study the effects of media on society, and in order to request better contents. Published both in vídeo and book formats (Memorias; i.e.: Proceedings), by the organizing association: Asociación A favor de lo mejor en los medios de comunicación, 1999.

Currently available at (repository): http://www.bettermedia.org

___ ___

NOTES:

The then president of Mexico: Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de León, inaugurated the conference in which this paper was delivered. The event took place at the Auditorio Nacional [National Auditorium], Mexico City, D.F. (a forum with seats for 10,000 personas), on April 21st and 22nd, 1999.

Work cited by:

Raúl Trejo Delarbre in “‘Medios’…: ¿Y qué es ‘lo mejor’?”, en Crónica, April, 21st, 1999.

Niceto Blázquez Fernández in Foro ético mundial y medios de comunicación, Ed. Visión Libros, 2006; page 20.